Research finds 'defining' childhood portrait of Marie Antoinette is really her sister

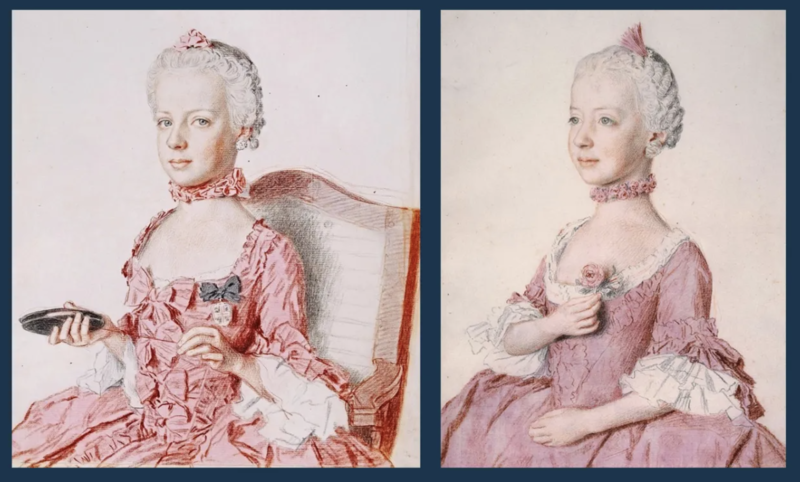

The most famous portrait of Marie Antoinette as a child is really of her sister, according to new research.

Professor Catriona Seth of Oxford University’s Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages made the discovery while researching a book and working with the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire (MAH) in Geneva.

The distinctive drawing by the Swiss painter Jean Etienne Liotard in 1762 has helped to shape the way we think of the last Queen of France in her early years.

She is depicted as a seven-year-old, holding a shuttle used for weaving and staring directly at the viewer with a determined look in her eyes.

This has long been thought to demonstrate that the future Queen was destined for a life of significance. For example, a 2015 Guardian review of a Liotard exhibition singled out the portrait:

“The 1700s were an age of revolution in life and thought. The violent climax of that revolution is foreseen here, eerily, in a portrait of the future Queen Marie Antoinette of France when she was a seven-year-old Austrian princess. She looks assured and confident. She will die at the guillotine.”

But through close examination of Liotard’s portraiture and archival research, Professor Seth has revealed the portrait is likely to be of her older sister Maria Carolina, who later became Queen of Naples.

Instead, Professor Seth has identified another girl in the same collection of Liotard’s portraits as Marie Antoinette – but this gives a very different impression, as she is holding up a single rose and smiling demurely as she looks to the side.

Professor Seth said: “I have always been fascinated by the picture said to be of Marie Antoinette as a child and even used it on the cover of a book I wrote 20 years ago. But while researching my latest book which centres on portraits of Marie Antoinette, something was niggling at me, so I went back to the MAH in Geneva to look more closely at Liotard’s full collection of portraits of Marie Antoinette and 10 of her siblings”.

“The first clue came from what was thought to be a brooch worn by ‘Marie Antoinette’ in the portrait. The girl is wearing the medal of a specific order of chivalry which was conferred on Marie Antoinette and her sisters”, explained Professor Seth.

“But I realised Marie Antoinette, as the youngest sibling, did not receive hers until nearly four years after the portrait was taken – while Maria Carolina was awarded hers in 1762, when Liotard was in Vienna painting the imperial family. I worked out there had to have been a switch with the younger-looking child in one of the other portraits being Marie Antoinette, rather than Maria Carolina. “

Professor Seth added: “The girl is wearing distinctive earrings that I managed to find in a subsequent picture of the queen of France. She is also holding a rose, which is a recurring feature of portraits of Marie Antoinette throughout her life.”

At the MAH, the identification of individuals in portraits, notably when this might rely on accessories, was already drawing the attention of Dr Marie-Eve Celio, senior curator and head of the graphic arts collection.

“I was very excited about Professor Seth’s discovery,” said Dr Celio. “At the MAH we have been investigating the provenance and the materiality of this prestigious series. We found out that the identity of the two sisters was already mixed up when these drawings entered the museum in 1947 thanks to the generosity of the “Société auxiliaire du Musée” (today “Société des Amis du Musée d'Art et d'Histoire”) and the “Gottfried Keller Stiftung”.”

Working together, Professor Seth and Dr Celio have been inspired by this discovery to start a project looking at how we can better authenticate historical portraits by using a mixture of AI and archival research. It has led to a new research collaboration, called “INTERART project” between Oxford University, the MAH in Geneva, Idiap Research Institute, as well as the School of Criminal Justice of the University of Lausanne.

“There have long been challenges to the accurate authentication of portraits,” Dr Celio said. “We look at and compare for example the colours of the subjects’ eyes, but the pigments can change over time which means we don’t necessarily see what the artist meant.”

“AI could transform how we look at portraits and people if we train it to assess how faces change with age or how different artists represent the same face,” said Professor Seth. “For example, if someone claims to have discovered a new portrait of Shakespeare, AI might learn from authenticated portraits of him to project how his face would have looked at the right time for the newly claimed identification.”

Further information on the INTERART project will be released later this year, while the new exhibition of Liotard’s portraits is expected at the MAH in the autumn of 2026. Marc-Olivier Wahler, director at the MAH said: “While these remarkable portraits have been on display many times over the last 250 years, it will be extra special to see Marie Antoinette as she actually was, rather than mistaking her for her sister! It is so exciting to find out more about this major artist and I am very much looking forward to this fantastic interdisciplinary collaboration.”

Image credits:

Top left: Jean Etienne Liotard (1702-1789), Maria Carolina (1752-1814), purchased with the support of the Fondation Gottfried Keller and the Société auxiliaire du Musée, 1947, inv. 1947-0042 © MAH Musée d’art et d’histoire; photo: Bettina Jacot-Descombes

Top right: Jean Etienne Liotard (1702-1789), Marie-Antoinette (1755-1793), purchased with the support of the Fondation Gottfried Keller and the Société auxiliaire du Musée, 1947, inv. 1947-0041, © MAH Musée d’art et d’histoire; photo : Bettina Jacot-Descombes

Bottom right: Professor Seth (left) and Dr Celio (right), photo by Birgit Schmidt-Messner