Source: Robert-Havemann-Gesellschaft

Supervisor: Professor Karen Leeder, Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages

Project outline

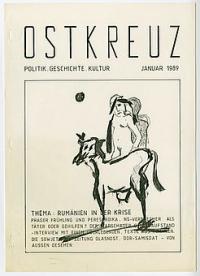

The samizdat sphere that flourished between c.1980-1990 in former East Germany produced an extraordinary flowering of hundreds of tiny magazines and graphic/poetry journals that evaded the strict censorship of the state. The artists, musicians and writers who produced them lived mostly illegally in the rundown housing stock of the major East German cities (especially Prenzlauer Berg in Berlin) and created a Bohemian enclave within the dictatorship, which still has influence today.

The magazines began life as an alternative outlet for those young artists forbidden from publishing in the highly regulated public sphere: unique, experimental, hand-crafted pieces with occasional poems, photos, perforations, paintings, collages and sculptures. These were passed from hand-to-hand at the illegal readings, salons, exhibitions and back-room gigs. They created and sustained an alternative public sphere under Communism, a network of artists that gave a sense of identity and solidarity in often dangerous situations (several writers were imprisoned, others driven to suicide by the secret police). Over the course of the decade the magazines became more formalised with larger circulation and new technologies and developed their own particular identities and rivalries. Many became associated with political causes (environmentalism, the church, the nascent civil movement) and some of the most popular engaged in theoretical reflection on the avant-garde, language and power etc.

These magazines quickly became valuable and sought-after collectors’ pieces in the West telling an interesting story about literature, publication and the market; the Taylor Institution in Oxford (uniquely in the UK) acquired some. The story is made more complicated (and more interesting) by the fact that after the end of the GDR this sphere was briefly celebrated as the only ‘authentic’ literary product of the socialist state. Some of its key representatives became heroes and were lauded internationally. Only two years later, however, it was discovered that this scene had been infiltrated, even possibly steered, by the literary section of the secret police, in order to channel energies that might otherwise prove politically disruptive.

This project then will use the magazines (now largely catalogued), along with films, Stasi records and eye-witness accounts to address this sphere: its development; the myths that surround it; the often fraught community it created; its relationship with overt and covert authority; the aesthetic developments that came out of it (it launched the careers of a number of major poets and artists in Germany today) and its relationship with other avant-gardes. What is more: it offers a unique case study in publication beyond print from its beginnings to its end. The Taylor Institution Library at Oxford has a full bibliography of relevant material. Thirty years after this experiment ended, the legacy is ripe for rethinking.