The Dynamics of Publication on Stone in Democracies and Oligarchies

Supervisors: Professor Rosalind Thomas, and Professor Nikolaos Papazarkadas, Faculty of Classics

Project outline

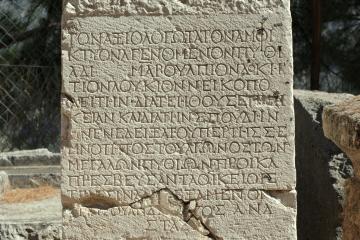

In ancient Greece, the most striking form of ‘publication’ of texts was the stone inscription, which literally ‘made public’ various forms of text on stone in a public place. Inscriptions lie at the core of many – but not all – Greek communities, and the habit of inscribing has been called the ‘epigraphic habit’ (Macmullen), to underline that it is culturally and politically determined. Some city-states published laws and city decrees on stone extensively. These form fundamental evidence for the historian, but much more thought can be devoted to the nature of this type of publication and its implications for the forming of a political community. The fact that important public documents were inscribed on stone in many cities leaves the modern enquirer with an extremely rich body of evidence: at the core lie ideals of public proof, accountability and public knowledge, and not only in democracies. This can challenge certain modern assumptions about accountability.

The democratic impetus for this form of publication has been most discussed for classical Athens, 5-4th.c. B.C. (Hedrick 1999 on ‘disclosure formulae’, Thomas 1992, Liddell), but there is not complete consensus that democratic accountability was the main or only explanation for the numerous Athenian inscriptions. There remain other questions also: how far were certain documents set up for civic, democratic purposes, how far for accountability before the gods; why were accounts often inscribed extravagantly and at length, and how do these inscriptions compare with other civic documents on stone, and other display purposes. Furthermore, a strand of modern scholarship stresses the presence of all important civic documents in the archives (on wood or papyrus), and claims that they were easily accessible (Sickinger): this implicitly modernizing view leaves the nature and purpose of the huge stone inscriptions even more striking, and requiring renewed examination. New evidence for documents on bronze tablets (Argos, Thebes) is also thought-provoking The symbolic value of having public documents visible on stone also deserves more research, as does the question of how far inscriptions validate the law, decree or treaty by their very existence, and for how long. For all these questions, the placing and appearance as well as written content need examining.

It is also time to move beyond Athens and its particularly democratic ideals to extend discussion. With many more inscriptions appearing from other cities, and certain large corpora published or about to be published (Boiotia, Thebes, Argos), the time is ripe to investigate what kind of political community – if any – is conveyed by the public inscriptions elsewhere than Athens. And what are the implications of a city-state whose public inscriptions consist mainly of honours to individuals? Recent work on Thebes, for instance (Papazarkadas 2016), suggests further elaborations of the epigraphic habit, and this meshes in interesting ways with the question about political community. The late classical/early Hellenistic phenomenon of the archive wall – a wall of selected documents published on stone – is also prime evidence for this question. A sub-section of this concerns what we may call ‘prestige inscriptions’: inscriptions of very high quality and high visibility, carefully created with superb workmanship and elegance. Where do we tend to find these and why were some inscriptions treated so expensively, while others were not?

While Benedict Anderson claimed for the modern world that a public sphere depended on print readers, we should ask how far public inscriptions conveyed a sense of the ‘public sphere’ for many (or most) Greek cities, and if so, what kind of public sphere. This holds whether or not public inscriptions were read merely by select individuals, or read aloud, or mainly seen as monuments.

The increasing digitization of certain epigraphic corpora makes this research far easier for some areas (Epidoc). The Classics Faculty’s Epigraphic seminar, and CSAD, form a focus for research on inscriptions; and the Workshop for Manuscripts and Text Cultures, run from Queens College Oxford specializes particularly in stimulating comparative work on writing cultures of the Middle and Far East.