Practicum Placement: CLARIN-UK

Student Caitlin Wilson presenting on her practicum placement at the MSc in Digital Scholarship Symposium

By Caitlin Wilson (MS in Digital Scholarship student).

As part of the MSc in Digital Scholarship programme, students complete a practicum placement with an ongoing Digital Humanities project at the University during Trinity term. We, the MSc students, are offered a large selection of practicum projects from which to choose ranging from projects on Digital Innovation at the Pitt Rivers Museum to digitising the correspondences of Catherine the Great, and many more.

Coming from a linguistics background, I chose to undertake a placement with CLARIN-UK, the Common Language Resources and Technology Infrastructure. CLARIN is an international digital infrastructure that provides access to a wide range of language data and tools that aim to aid research in the social sciences, humanities, and further. During my placement I learned a great deal about the structure and inner workings of CLARIN and other research consortia as well as the specific practical tools I would need for building a digital corpus. With Dr Martin Wynne as my supervisor, we decided that the main goal of the placement should be to produce a multilingual corpus of oral testimonies of the Holocaust to which corpus linguistics research methods could be applied.

Our project started with around 100 testimonies of Holocaust survivors that were kindly shared with us by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Investigations were initially made to find out which of the testimonies were accompanied by complete transcripts, as this project would only focus on text and would not undertake the task of manual transcription or make use of automatic speech-to-text technology.

Post inspection, there remained around 50 transcripts in 5 languages: English, Russian, Polish, Czech, and Hungarian. These could then move on to the next stage of preparation: cleaning. The transcript files, originally in JSON format, were cleaned to remove any unnecessary text or metadata (USHMM had occasionally included time stamps and rights and restriction notices at various intervals in the text). Cleaning was done with a combination of XML scripts and global ‘find and replace’ functions. The output files contained only the text ID and transcript of the interview structured using sentence and utterance boundaries. All other metadata was extracted and stored in separate files.

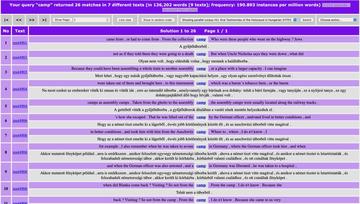

The next step involved parsing the files with various parsing tools to allow for syntactic information about each word in the transcript to be added. The tools used were NTLK, spaCy, TreeTagger, RNNTagger, and stanza. These were implemented either via command-line code or through Python packages. The output of this process was files in VRT format (one word per line) with each word accompanied by its part-of-speech tag and lemma. Non-English files were also translated using DeepL and parsed using the aforementioned tools. The files were then uploaded to CQPWeb (translated files were aligned with the originals) in various sub-corpora organised by language.

Concordance from the Hungarian-English aligned corpus of testimonies.

The resultant corpora uploaded to CQPWeb demonstrate how Holocaust researchers can utilise corpus linguistics tools to perform searches on a large number of testimonies at once. Whether researching individual words and the contexts in which they are spoken, or understanding the type of language that survivors use when discussing traumatic events, corpus linguistics can allow researchers to gain a better understanding of overall themes and trends in testimonies. This in turn allows for users to zoom in to individual texts and perform a more informed close reading.

Further discussion has now led us to identify areas of improvement for the corpus, notably seeking a universal syntactic parser that could produce universal part of speech tags that are identical across all language. Using the Universal Dependency guidelines was deemed to be the most appropriate course of action as it would allow for all texts in the corpus to be searchable by syntactic category at once. Other options including semantic tagging and named entity recognition were also considered as possible ways of enriching the corpus. Lastly, far more than 50 testimonies are needed to allow for researchers to gain a real understanding of the full breadth of realities experienced by those who lived under the Third Reich.

My time working with CLARIN has taught me a lot about the intricacies and complicated politics of research consortia and the importance of interdisciplinary research. A linguist or a historian alone could not have produced the outcomes of this project. Rather, close collaboration, discussion, and sharing of ideas and data allowed for us to envision a new way in which to approach Holocaust and oral history studies. I have also learned that language data and tools are not limited to linguists. Researchers from many fields across the Humanities and more can make use of these type of data to enrich their research. While Holocaust historians may shy away from corpus work and computational tools, for fear of losing the individual voices of their subjects, I do believe that implementing distant reading methods and gathering quantitative data can help researchers improve their understanding of individual cases and study each testimony with a more holistic approach.

The overall outcome of the placement was highly positive, the pilot project itself had a positive outcome. The hopes are that with time, more feedback, and more data, an improved version of the corpus can be uploaded to CQPWeb.

This is an edited version of a blog post on the CLARIN-UK website.